FINDING YOUR FEET WHEN THE WATERS ARE TROUBLED - Jasmin Pittman Morrell

Sitting on the counter in my grandmother’s kitchen, the afternoon sun blankets my back from the window behind me. My knees are pulled into my chest, and my toes hang just over the edge of the counter. Beside me, she is chopping carrots, onions, and green peppers for the meatloaf we will have for dinner. When she finishes, she pulls a cast iron skillet from one of her cabinets, and sets it on the stove to heat up. She takes a block of butter from the refrigerator, slices off a pat or two, and tosses it into the warming skillet. Once the butter is bubbling, in one swift motion she brushes the vegetables with one hand from the cutting board into the pan. There is a sureness and a knowing in the way she moves around her kitchen, and without disrupting her rhythm, she reaches into the cookie jar, hands me a gingerbread man, and kisses my forehead.

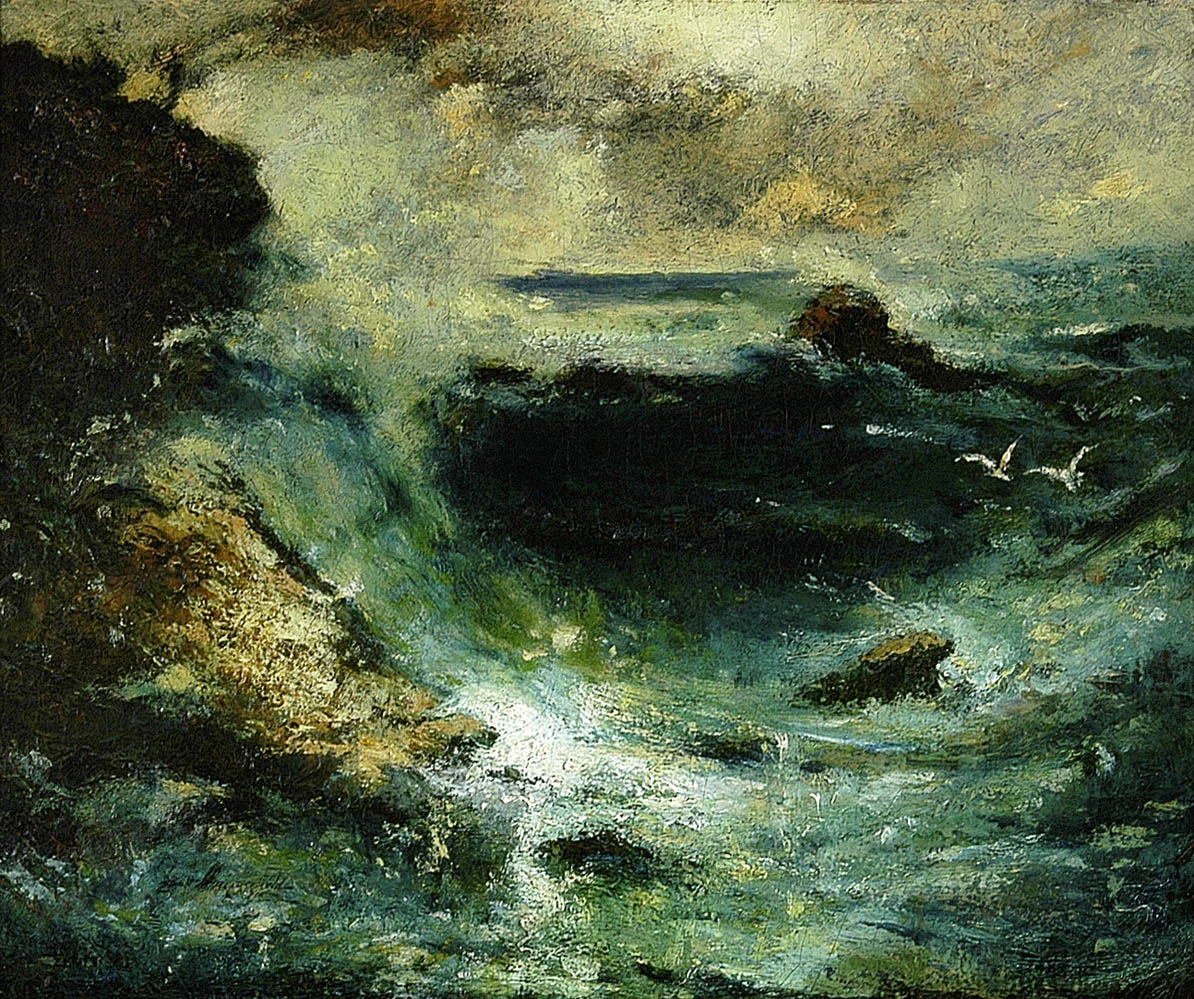

Wade in the water, she sings under her breath, almost to herself. Wade in the water, children. Wade in the water. God’s gonna trouble the water.

As a young child, I did not know that my enslaved ancestors sang this song in the night, to help light the path of liberation for each other. I did not know that my grandmother’s mother, and her mother before her, carried this melody on their lips and in their blood. I did not know that my grandmother sang this when she needed the comfort of remembering a time when she felt small and safe, sitting in a kitchen while food was being prepared. I did not understand how singing songs could save them.

There’s much I still don’t understand. I’ve recently moved to the mountains of Southern Appalachia, a place that feels so resonant that it almost hums in my body, a place dotted with my family’s history, particularly my mother’s family. The land is familiar, in a long, old way of recognition. As I walk the city streets or venture out to hike the hills, I look around thinking, this is home. And yet. I’m still feeling displaced.

It’s home, but also not quite home. I don’t always remember my way to the grocery store. I don’t run into people I know when I run errands. A plant in my yard I did not recognize gave me hives. It tends to be cloudier here, and my mood has dipped from the lack of sunlight. My heart may know it’s home here, but my body has not yet adjusted to life’s new rhythms.

In much the same way, I look around at this country and know that I belong to it. My people were forced to pick cotton here, their sweat and blood quenching the thirst of Empire. My people emigrated here, Irish settlers who were the first to live on America’s original mountainous frontier because they were poor and that was where land was cheapest. And some of my people were simply already here, living in fluency with the earth and sky, before they were massacred, the survivors forced away from the land they honored and cherished. I’m as American as it comes. This place, and my intimate relationship with its marginalization and oppression, is in my blood.

And yet.

I’m still feeling displaced in this particular moment of our nation’s history. How can this be my home? I often find myself wondering. I wonder, despite the knowledge that the beast of white supremacy is also as American as it comes.

The stories of my people, my own personal family history, have nearly vanished as many of the elders have died and their children live lives disconnected from each other. Though my memories of my grandmother are everything memories of a grandmother should be—idyllic, warm, and comforting—I wish I knew more of her story. I want to know what it was like for her to be a young Black woman attending college in Greensboro, North Carolina in the late 1940s. I want to know what it was like to marry a man with drive and ambition, despite—or perhaps because of—the color of his skin. I want to know what it was like for her to be a housewife in the 50s, living in a white neighborhood, and sending her children to be among the first to desegregate white schools in the area.

I want to know these things because I am fairly certain my grandmother was something of a heroine in the face of her own particular moment in this nation’s history. I want to know that I inherited her courage, her dignity, and her grace. I want to know how she formed community; if she wore a mask to hide her vulnerabilities, similar to the one Paul Laurence Dunbar so elegantly describes in his poem, “We Wear the Mask:”

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

That hides our cheeks and shades our eyes…

We smile, but, O great Christ our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise…

We wear the mask.

I want to know all the tiny facets of her beautiful, full-dimensioned humanity.

Our country has been beset with troubles since its inception, with power and greed and patriarchy doing what power and greed and patriarchy do. We see the consequences—in the environment, in impoverished communities, and in the politics of calculated indifference. But we also see the people who rise up to resist, to advocate change, to write poetry, to serve as healers. There are hallowed names in that canon, names like Phyllis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and bell hooks. They are bright lights that we can look to for inspiration and for hope; to absorb their stories is powerful, almost as if by osmosis we can better learn how to grieve, heal, and mend the breaches that divide us.

And: It’s become equally important for me to chase the desire for stories of those whose names aren’t well known, names no one may ever really know. Women like my grandmother, or perhaps yours, who may not have been on the front lines of change, but whose presence and quiet perseverance made a difference in her community. I dream that as we continue to move through history, we’ll find our feet, discovering our balance: even in unexpected, mundane places like kitchens—cooking in rhythm, singing songs of liberation; echoing our past and informing our future.