THE REFRAIN CANNOT BE UNSUNG - Kim Ruehl

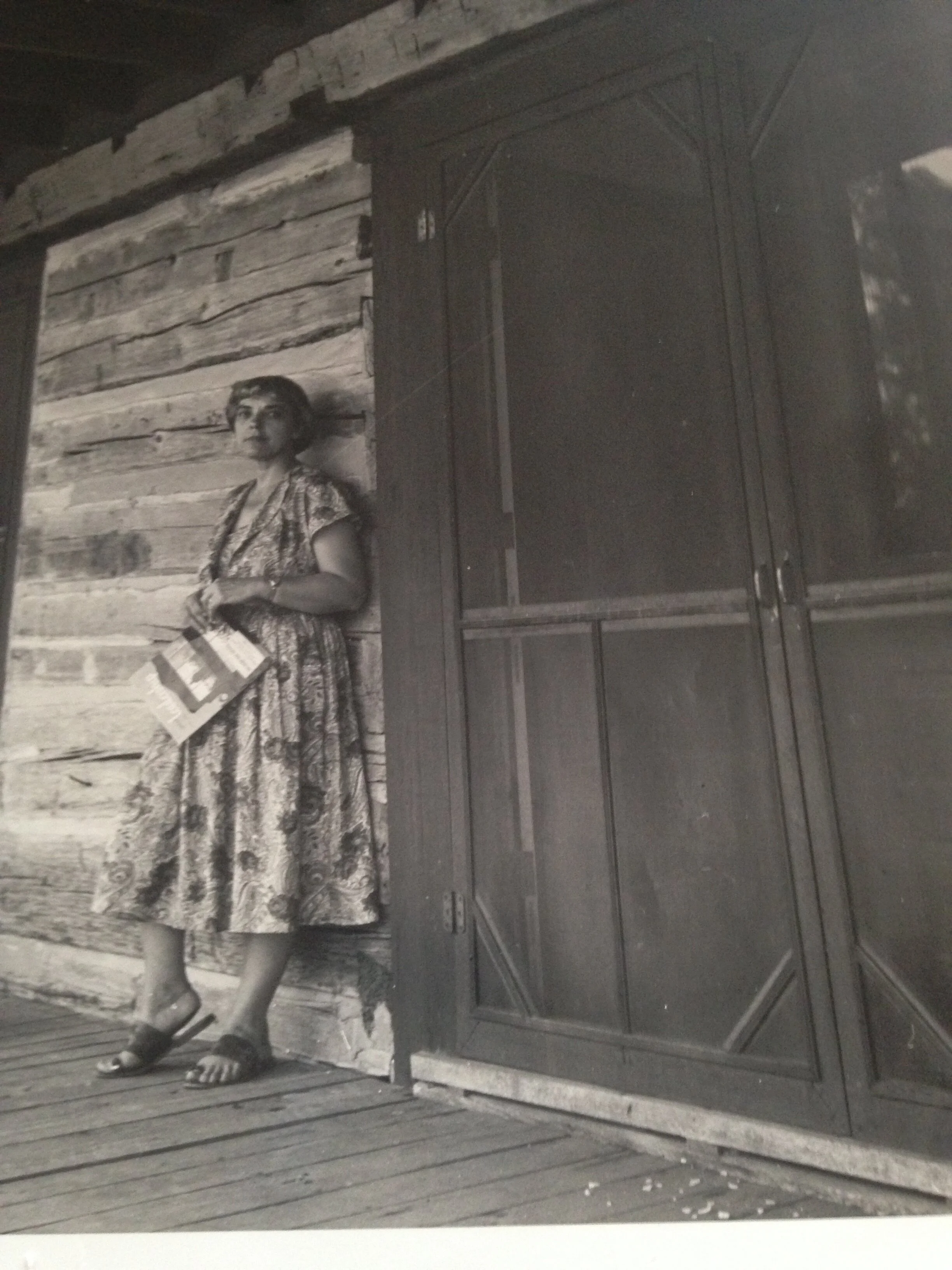

In February 1935, Zilphia Mae Johnson was estranged from her family and eager for a life beyond her hometown of Paris, Arkansas. Her friend, Presbyterian minister Claude C. Williams, recommended she attend a six-week workshop at a new school for adults in rural Monteagle, Tennessee. Highlander Folk School had been open just over two years and was still finding its feet. Its founder, Myles Horton, had a clear vision about the school’s educational program, but was looking for someone to build its culture. He found that person in Zilphia. The couple married quickly and, over the next two decades, Zilphia built a culture at Highlander that underpins the school’s existence even now—more than a half-century later. She collected hundreds of folk songs and repurposed them for use in movements. She built a dramatics program that was a foundation for Highlander’s influential role-playing curriculum. And she became a beloved figure in both the labor and the burgeoning civil rights movements.

Then, in the spring of 1956, she suffered a shocking, tragic accident that ended her life just as the civil rights work she and Myles had assisted for years began to prove fruitful. The story of how they built Highlander together fell into the rearview as their vital work continued. And though several books have been written about Myles’s contributions, none have existed about Zilphia until now.

I spent a decade studying her life and work for A Singing Army: Zilphia Horton and the Highlander Folk School, which is out now via University of Texas Press. Following is an excerpt about her role in introducing “We Shall Overcome” to the labor movement:

The newspaper reported: “Most of the machines at the American Tobacco company’s plant ground to a stop shortly after noon today when some 1,000 employees . . . walked out of the factory at the direction of Local 15 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers Union.”

It was unseasonably warm on October 22, but as autumn 1945 unfolded, the air turned chilly and humid in Charleston, giving way to a colder, wetter winter. For the women of American Tobacco’s FTA-CIO, it was not the best season for a strike, but that they were willing to stand out in the cold rain in order to make a point indicated that other, more comfortable avenues toward success had failed.

These women knew, because they had organized with the CIO, that people elsewhere were making more money for the same job. They knew that there were laws in the United States that ensured factory workers a fair wage and a safe workplace. This may have been the City of Charleston’s first labor union strike, but they were fighting on the tail end of the labor movement’s heyday, long after the eight-hour workday had been won, and after Roosevelt’s New Deal had ensured protections for union workers.

They knew there was nothing to lose. They saw it in the eyes of their children, who were hungry and poor, who wanted more, who would eventually take up the cause and face beatings and worse to bring the battle for civil rights to the national stage. It would be easy, on this side of history, to imagine that these women had all that in mind, and perhaps they did. But, more immediately, they wanted good pay and respect. They struck for five months that winter.

At first, the decision to strike takes some cajoling, but once everyone’s on board, there’s a passion, a wave that passes over people. A sense that, we can do this, together. These women showed up day after day, refusing to work, not taking home any pay. Lillie Mae Marsh Doster remembers being on the picket line from six in the morning until six at night, every day, from October to March, except one: Easter Monday.

She, her fellow union steward Lucille Simmons, and the others didn’t have savings to tap. As the days dragged on into weeks and then months, the bosses refused to cave and the rain refused to quit.

When Pete Seeger told his version of this story to Tim Robbins for Pacifica Radio in 2006, he placed them standing around a big metal drum with a fire burning in it for warmth, asking each other, Is this strike sustainable? How do we know when we should we give up?

Discouraged, broke, demoralized, some picketers started going back to work, willing to take the fifteen cents an hour the company offered them as a consolation. Other strikers felt angry and betrayed, some threatening the “scabs” with violence.

“Some of the girls didn’t want to come in through the front door,” Doster said, “because we were picketing. Because, I mean, they put the beating on some of those girls one day.”

Those who decided to defy the strike and return to work would sneak in through the back door to avoid any altercations. Hundreds of others remained on the line, though, huddled in soup kitchens for warmth and subsisting on spare change from fellow workers, who sent them funds via the CIO.

Simmons closed each picketing day by singing out, long and slow, low and haunting, like a meditation, an old, old hymn with new words:

We’ll be all right

We’ll be all right

We’ll be all right someday

Whoever was there, huddled in the cold, holding their coats together across their chests, joined in. Simmons insisted they couldn’t leave until they sang. “Every afternoon we would fuss with Lucille,” said Doster. They had been on their feet all day and rolled their eyes at her persistence. But, once she started singing, they relented and joined in. There was something about the song that just refueled them.

Down in my heart

I do believe

We’ll overcome someday

“You think about that, it’s almost like a prayer of relief,” Doster explained. “We didn’t make up the song. We just started singing it as a struggle song.”

“We sang ‘I’ll be all right . . . we will win our rights . . . we will win this fight . . . we will organize . . . we will overcome.’ We sang it with a clap and a shout until sometimes the cops would quiet us down.”

Simmons’s approach to this old melody and lyric was likely drawn from “If My Jesus Wills,” a hymn written by Louise Shropshire sometime in the 1930s. Shropshire was a Black woman who was born to a sharecropper family in Alabama but grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. She sang with and composed hymns for the choir at her local Baptist church.

For decades, the history of this song was traced to a white man named Charles Tindley, who published a song called “I’ll Overcome Someday” in 1901. Though the spirit of Tindley’s song is similar, it doesn’t match “We Shall Overcome” in lyrical or melodic pattern, while Shropshire’s composition is almost exactly the song that came to Zilphia Horton from the women of American Tobacco. Its melody can be traced back to a Catholic hymn from the Middle Ages, “O Sanctissima,” and had likely been through a hundred lyrical incarnations before Shropshire’s update.

Regardless, as those five months passed, the song became somewhat of a theme for the strike. While the union did not achieve all its demands from the American Tobacco Company, the workers were successful in winning a slight pay raise. They also experienced the power of singing, using parts of their culture to change the conversation, to empower themselves and each other, and to fuel their resistance day in and day out.

When the strike ended on March 31, 1946, Doster, Simmons, and the others returned to work, but they had changed. They had not prevailed in their demands. In fact, what amounted to a less-than-successful strike is perhaps one of the most important parts of their story. The eight-cent raise they were granted was far lower than the twenty-five cents they were demanding, but the women of American Tobacco had learned a vital lesson through this momentary failure. They hungered for a better way and now knew one was possible. They knew from experience now that when they organized, people in power would listen and respond. This would carry the Black population of Charleston through other labor disputes and into the thick of the civil rights era on the wings of the experience they now had with collective power.

Though history has lost track of Simmons’s story, Doster became heavily involved in the civil rights movement that unfolded in the ensuing years, helping to organize Black nurses in Charleston and working with other groups to lift their voices and overcome. A couple of their coworkers from American Tobacco traveled to Monteagle to attend a workshop at Highlander that summer after the strike. Accounts about who, exactly, brought the song and how it even came up during a Highlander workshop vary.

In a pamphlet written in the 1970s about the history of what by then was the unofficial anthem of the civil rights movement, Guy and Candie Carawan shared the version of the story they had been told. Neither was present for that 1946 workshop, but it is possible that at least part of the story Guy picked up was direct from Zilphia, if not from Myles. Both Hortons were prone to exaggerate their stories in order to make a point, though, so it’s hard to know what details are accurate.

Regardless, as Guy recalled:

It is one of the ironies of history that the song was brought by two white workers, who had probably not sung it themselves but had heard it sung by the black strikers. … Zilphia had to ask several times before the Charleston workers told about “We Will Overcome,” and based on their rendition of it she had to imagine what it must have sounded like in black tradition on the picket line. … It had a slow, free, anthem-like feeling to it, and wherever she taught it people loved the song.

The “slow, free, anthem-like feeling” is certainly an accurate description of the recordings Zilphia made with her home-recording device. But the memory that it had been brought to Highlander by white workers from American Tobacco is the point that’s likely not true, as intriguing an irony as it may have been.

Other sources point to the likelihood that the Charleston FTA-CIO workers who taught the song to Zilphia were Black. Some reports suggest that it was Simmons and a woman named Delphine Brown who delivered the song. Brown was also known for leading the song on the picket, though she attacked it with a more spirited tempo than that of Simmons’s drawn-out dirge.

Aleine Austin, who was present on the plateau that year, told Highlander interviewer Sue Thrasher in 1982:

It was a mixed group; and part of the program was just having them describe what their problems were. They had just had a strike and they were describing the conditions of the strike and then they … started singing some of the songs they sang on the picket line. And one of the songs was [she sings] “We shall overcome; we shall overcome.” And then “The union will see us through, the union will see us through.” And the final verse, “We are on to victory, we are on to victory.” And Zilphia just felt the power of that song, “We shall overcome.” That first verse, but the rest of it was sort of banal and you know, she got us together one night and told us how powerful she felt this song was and she played it on the piano with the chords, and … the whole workshop was there, and she said, “I think we could find better words for some of those middle verses.” She says, “So why doesn’t each person here—now that you know the melody—sit down and write what you think would be a good verse?” And so we sat there and then each of us sang our little portion. Well, there [were] marvelous lines that came out of it. I think one of them was “The truth will set us free.” That was Myles. I’m not sure, but I think that was Myles.

*

Zilphia’s sister, Ermon Fay, meanwhile, remembered going into the Highlander library with Zilphia and the two FTA-CIO workers and coming up with new verses, just the four of them. Perhaps somewhere in the center of the Venn diagram of these memories lies the truth about how “We Will Overcome” was reborn at Highlander.

One thing all the memories have in common is that several people came together at the Highlander Folk School in spring 1946, under Zilphia’s leadership and encouragement, and metamorphosed this hymn into a song that would ultimately change the world.

Zilphia knew an important song when she heard it. She adopted “We Will Overcome” as a sort of personal anthem, printing it in song sheet broadsides. From that moment on, she taught it to everyone who came through Highlander. She closed every meeting with it. She sang it as a sort of closing prayer at every event and gathering when a song seemed necessary. The song struck a perfect balance between public declaration and personal meditation. It was a reminder to all those listening of the persistence of the human spirit, just as it was a reminder to the singer that no momentary struggle could kill a person.

As long as I’m alive, the song seemed to say, I can sing this song.

Every word in the song was important. Every note, drawn out the way she sang them, was like a boldfaced underline.

We.

Will.

Overcome.

The song was effective because it did what it said it was going to do. For every individual singing along with the refrain, it was easy to feel that injustice both could and would be overcome.

Sing the song in a group and look around the room. Noticing other people sing the words, “we will overcome,” you begin to understand, intrinsically, without epiphany, that you want to overcome. A light turns on in your soul, showing you the truth of your humanity: You are not interested in resignation. As you sing “we” with everyone else singing “we,” you understand you are making a promise together, to one another, to yourselves, to anyone listening. There doesn’t even need to be eye contact because you hear these voices.

Not “we can overcome,” but “we will.”

By the end of the song, those singing are indelibly linked. The promise has been made. The refrain cannot be unsung. There is a knowledge shared with the others who sing, and with anyone standing nearby.

Being present for “We Will Overcome” means bearing witness to the power of collective determination. Together, the song tells us, we will transform the impossible into the accomplished. Indeed, that is the story of human history—from migration around the globe to the building of civilization, the pursuit of freedom and equity, and the exploration of space.

Humans are social creatures, not just because we enjoy each other’s company, but also because we cannot do much alone. We cannot survive alone, and we certainly cannot build a more just, peaceful, and equitable world alone.

The vitality of cultural organizing, the way that Zilphia developed the discipline, cut to the core of this truth about our common humanity: Organizing a successful movement is practice for the way the world will be once that movement is successful. The labor movement organized by empowering working-class people, teaching them how to be leaders, and illustrating to them the value of their knowledge and experience--things that would become necessary for them to employ when they wielded more power in the workplace.

The civil rights movement was organized by bringing Black folks together with white, to strategize, to see in one another the value of shared experience—something that would become necessary once Jim Crow laws were off the books.

These movements remain ongoing, but the lessons these organizers learned and shared at various turning points remain for us to improve upon as we continue to organize around these goals. And where the narrative details of labor and civil rights history are confined to books and lecture series, the songs that came out of these movements can be recalled and employed without anyone in the room requiring an explanation. Without any necessary context. When we sing, we are joining our voices not only with those in the room, but also with all those who sang before.

As Zilphia impressed upon all the people to whom she taught “We Will Overcome,” singing it now connects us—the “we” here—to those who sang it before, at Highlander, in Charleston, or anywhere else. When we sing, we join the long chain of people who saw no other way but to come together and promise to overcome. We are joined to their successes and thus the way forward becomes clearer.

In autumn 1948, in New York, Zilphia taught the song to Pete Seeger, who remembered her singing it “slower than anyone had ever heard it.” It’s easy to imagine the pair of them sitting together in a room, Zilphia singing it for Seeger with no accompaniment, Seeger picking up his banjo and finding a melodic rhythm that felt like a match. … Whether Zilphia knew she was setting the foundation for what would become one of the most consequential songs of the twentieth century is unclear. But she certainly believed it was one of the most important songs she had ever heard—if not the most important.

In 1947, the year before she taught the song to Seeger, she spoke to a gathering of CIO members about the importance of “We Will Overcome,” telling them:

“Although you may never have expressed these big world ideas in just the way we are talking about them tonight, I think that they are perhaps the reason you put such feeling into such simple words as we sing “We Will Overcome.”

For I think you know that it is only when working men and women everywhere realize not only their rights but their duties as union members, as citizens of a democracy, as citizens of a free world, and work together to that end, that we will overcome.

Kim Ruehl is a writer, editor, and folk music advocate based in Asheville, North Carolina. Former editor-in-chief of roots music magazine NO DEPRESSION, her book, A Singing Army: Zilphia Horton and the Highlander Folk School, is out now, from the University of Texas Press. It is the first biography of this woman who inspired thousands of working people, and left a legacy that changed the world.