Introduction

As an artist my work is ephemeral. Some of my pieces are very short-lived, swept up before the sun sets, while others may go undisturbed for days or weeks. WayFinding is the latter. Created in 14 hours over the span of 14 days, this piece remained up for seven weeks in the architectural gem known as Scott Chapel (Eero Saarinen) on the campus of Drake University. I approach deconstruction and construction of my art in the same way. They are two parts of a whole, separated by time, permanently linked by their transience. Here, everything that is ephemeral is a threshold to the infinite.

Much of my work explores the salvific nature of beauty and the relationship between beauty and brokenness. WayFinding came out of the need to name the brokenness and loss that my community (students, staff, faculty, and administration at Drake University) has sustained over the first 12 months of the pandemic. It also comes out of the need for orientation, the desire to find and be found by beauty.

These notes are like a museum docent - here to provide a little context, point to a few details, and hopefully deepen the visual experience of this offering. Thank you for engaging my work and giving me access to the sacred space between your ears.

I

Title

“WayFinding -

Searching for Beauty amid Brokenness and Loss”

Wayfinding is a method of navigation used by Polynesian sailors to find their way through vast stretches of open ocean. It would take several days to sail from one island to the next, disorientation would be deadly. Wayfinding uses the position of the stars, the movement of birds, and prevailing winds as a guide. This vital information was memorized and passed down from generation to generation in the form of story and song. The singing and the telling gave Polynesians clarity about where they were, who they were, and where they were headed. They listened to their past as if their future depended on it, because it did.

Searching for Beauty is an apt description of my creative process as an artist. The search is real because beauty does not always present itself. It cannot be conjured and refuses to be made permanent. Beauty never lasts. It only lingers, leaving the presence of its absence and a longing for more.

To be human is to live amid brokenness. It is part of the human condition, as inescapable as death, as perpetual as breathing. Brokenness brings a sudden end to wholeness; and then invites a deeper understanding of what it means to be whole.

The word loss is rooted in the Old English word losian, which means to become unable to find. Significant loss is disorienting; exponential loss is debilitating.

Meanwhile, being lost is a precondition to being found.

II

Guiding thoughts / questions

My creative process is often shaped by a handful of words, mostly questions. Here are a few that accompanied WayFinding:

• We have lost more than our sense of direction; we have lost confidence in the directions themselves.

• We have lost our sense of time and time itself.

• We have found uncertainty where we once held trust.

• We have lost things we didn’t know we could lose.

• We grieve in multiples - loss superimposed over loss.

• Scar as evidence of healing. Scar as compass.

• Is there a balm to be found in this thicket of loss?

• What story will take us to firmer ground?

• Whose silence waits to be heard?

• Can beauty restore wholeness? Again. And again.

III

Intention

The intent of this work is to name without words the brokenness and loss experienced by the Drake University community: global, national, communal, personal. It asks questions without uttering a sound; how do we move forward? When? And, in which direction?

IV

Materials

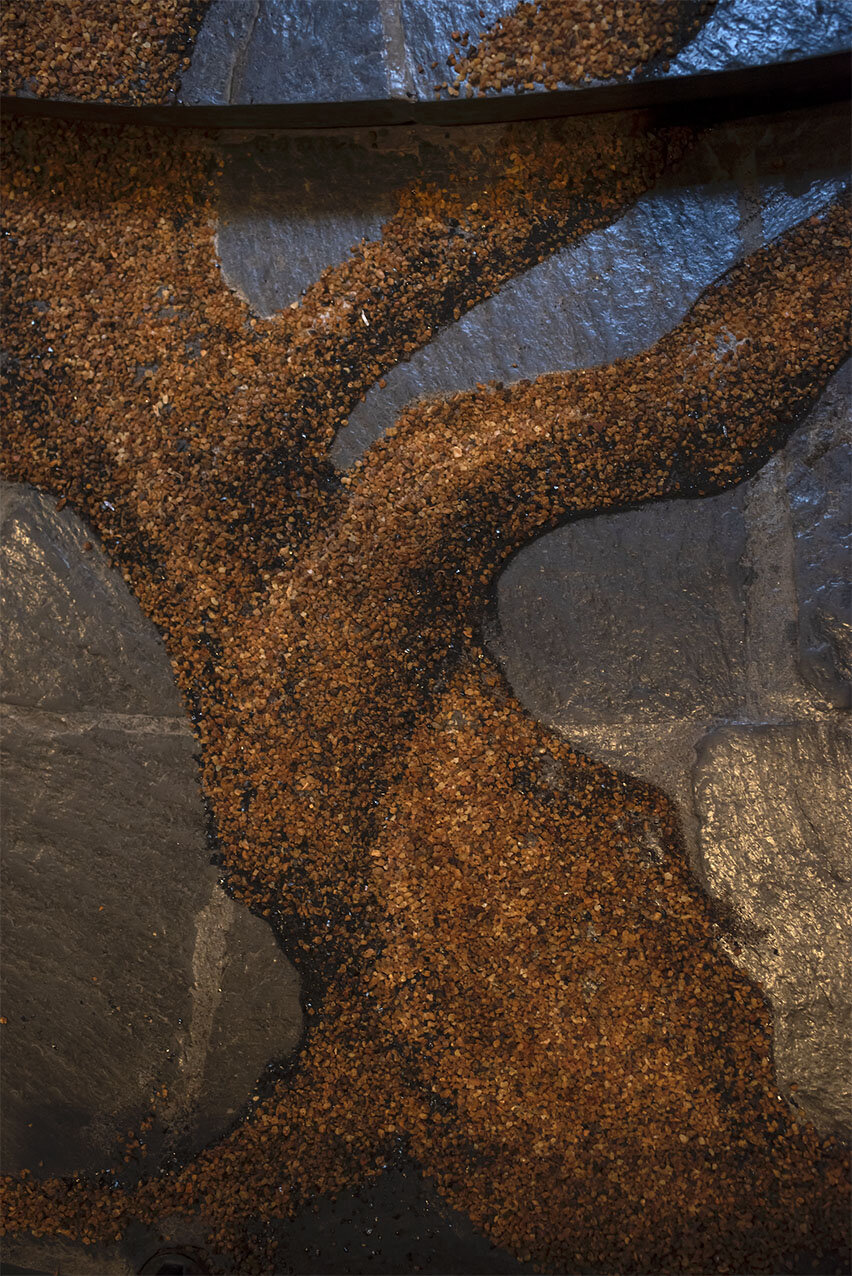

I use a variety of materials in my work but they all have at least two things in common: a compelling backstory that brings layers of meaning, and are multi-sensory (myrrh, for example, has wonderful aroma in addition to the warm hues: amber, burnt sienna, burnt umber). The four materials used here: myrrh, coal, glass, and sand, share an additional commonality, they are a product of brokenness.

Myrrh has a long history as both balm and burial spice in the ancient world. Myrrh is harvested by first wounding the rare tree (commiphora myrrha) causing the plant to secrete resin that staunches the wound protecting the tree and restoring it to wholeness. The dried tears of resin is later collected, processed, and sold by the ounce.

Granules can be burned as incense, distilled into oil, and added to wine (not to be recommended). Its medicinal properties include analgesic, anti septic, and anti-fungal. Ancient Egyptians used it for embalming mummies, and, according to legend, a star-gazing magi from Africa presented the costly perfume to an infant as a gift.

Glass and sand are different forms of the same compound, silicon dioxide (SiO2). It takes centuries for a granite mountain to produce a single grain of sand. The rough edges are worn smooth by the wind and water journey from summit to sea. Newly formed sand is sharp and irregular, old sand is round and uniform, (suitable for an hourglass). The sand used in WayFinding has several sources collected from four hemispheres. As an art material, sand crosses cultures, continents, and time periods: Navajo, Tibetan Buddhism, Aborigine.

At 3,200 degrees Fahrenheit, sand becomes glass.

At 24,000 pounds per square inch, glass shatters. It is impossible to predict the direction or depth of fractures as they spread through glass at 3,000mph.

Coal is fossilized plant matter that burned readily enough to fuel the Industrial Revolution. The environmental impact of coal emissions has been fully known for a long time. It is, by far, the leading contributor to anthropogenic climate change.

When crushed, it glistens like glass.

When compressed, it becomes a diamond.

When inhaled, it kills.

V

Context

WayFinding began on Inauguration Day (US) in the center of a university campus that sits on the unceded, ancestral land of the Ioway, Sauk, and Mesqwaki people in the middle of the middle of a deeply divided America on the brink of economic collapse, environmental catastrophe, unprecedented social upheaval, and a global pandemic. On any given day of 2020, brokenness was easy to see. Justice was not. If hope was lurking, it went largely undetected. While beauty, true to its nature, was begging to be found.

WayFinding ended in the middle of Black History Month (US), a time when the scars of white supremacy are made visible, pointing the way forward.

VI

Beauty

Beauty, like love, comes in many forms. Physical beauty is rooted in culture and fed by fashion. Aesthetic beauty is largely concerned with shape, color, and form.

The beauty for which I search is not confined to a culture or a time period. It dwells well below the surface, woven into the structure of the universe, turning up in nature and in numbers, as Fibonacci found.

Eero Saarinen’s design of Scott Chapel makes visible many of the numbers that would have been familiar to the Christian seminary students who studied at Drake and used the chapel in the 1950s and 60’s, (three, seven, and 12, for example, are all biblical). These numbers, however, are not exclusive to Christianity. Several of them hold significance in more than one belief system (7 is a prime example, found in Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Christianity).

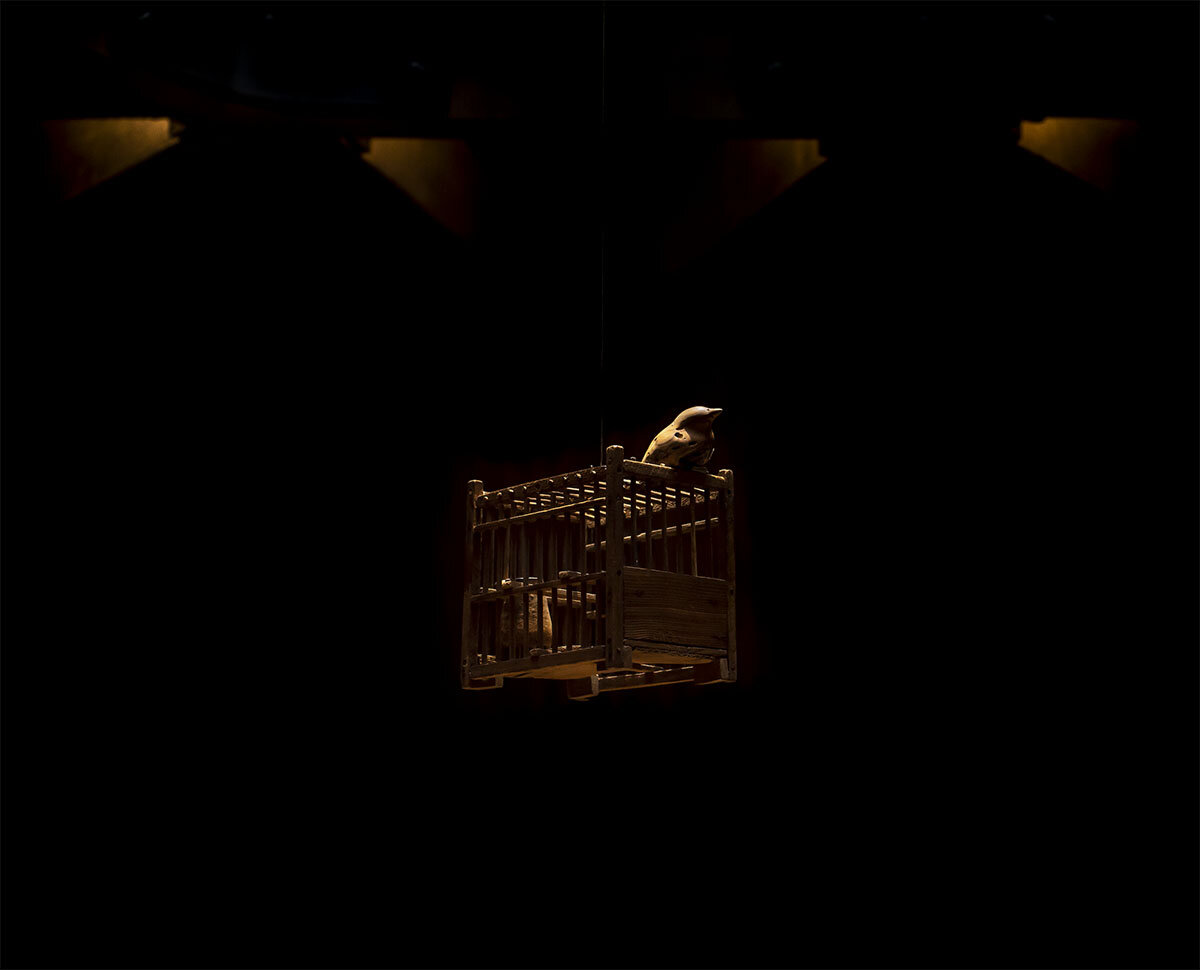

Some of the numbers at play in both the art (WayFinding) and architecture (Scott Chapel) are: two groups of 10 in pairs (high back chairs), 70 (skylight baffles), 12 (concentric circles of slate), seven (sided skylight, compass face, and entangled trees), four (hands, and materials: myrrh, coal, glass, sand), three (steps), and one (canary).

Symmetry can be defined as an equal distribution of parts. The left side of the lotus looks just like right side, in other words, balanced. For reasons buried deep in our biological history, human beings find symmetry beautiful. The admiration of this trait crosses boundaries of culture and spans the spectrum of time. Scott chapel is replete with symmetry, something echoed in WayFinding.

VII

Story

The small wooden cage suspended over hourglass and compass was once cradled under the arm of a West Virginia coal miner. For decades, miners on two continents clutched a caged canary (Serinus canaria domestica) as if it were a lifeline, because it was. These birds (usually female, as the males fetched a higher price aboveground), would accompany a miner into the pitch-black shaft to layer a melody over the percussion of a pickaxe. Toxic air quiets a canary before it kills a miner. Subterranean silence from the small cage meant that death was seeping in through the slag turning the coal mine into a tomb. A subterranean song from a bird the color of sunlight meant that life was still streaming, up above and down below.

As they worked, a coal miner listened to the bird as if their life depended on it, because it did.

The uncaged canary in Scott Chapel,

carved out of sugar maple and made hollow by powder-post beetles, has grown quiet.

In the bottom of Saarinen’s well and at the heart of this troubled planet there is a silence waiting to be heard, and a story willing to be found,

one that will lead us through this thicket of loss

toward firmer ground.

Ted Lyddon Hatten is an artist, theologian, and educator in Des Moines, Iowa, who works in ephemeral installation art, dry painting, and beeswax. His work has been seen at Yale Divinity School, Loyola University, San Fransisco Theological Seminary, and The Wild Goose Festival, and more.